Water Is the World’s Most Important Climate Sector - So Why Is It So Hard to Invest In?

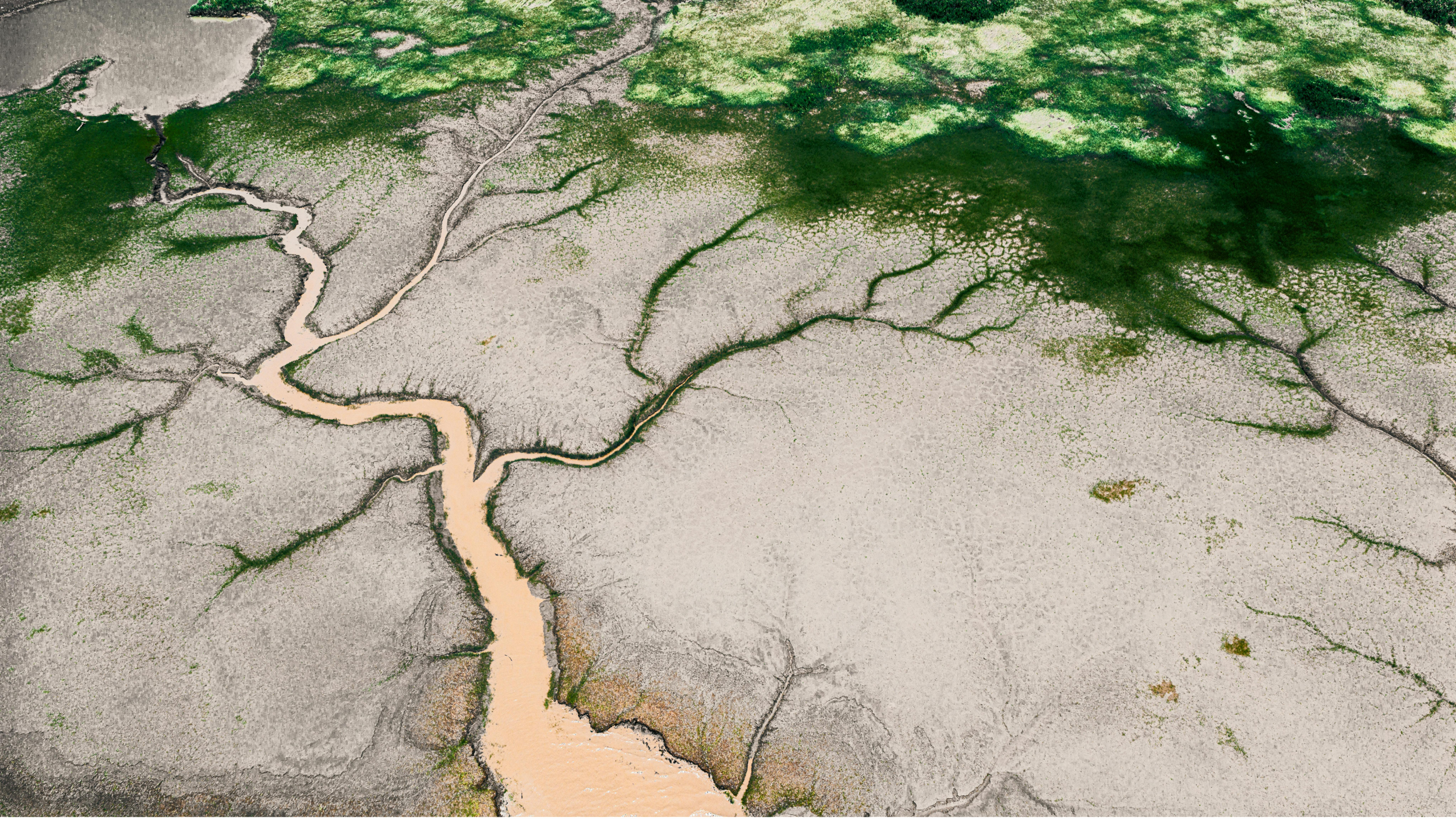

Water sits underneath every part of the climate transition - energy, food, cities, industry, and ecosystems. Yet in global investment markets, it remains chronically underfunded.

Floods, droughts, ageing infrastructure, and rising demand are already destabilising economies. But the real crisis isn’t technological - it’s financial.

As Emma Mee, Head of Membership at Green Angel Ventures, put it:

““Climate isn’t vertical - it’s horizontal. Everything crosses into everything else.””

And yet water, despite touching everything, continues to fall through the cracks.

That contradiction sat at the heart of a recent conversation, hosted by KAP, between:

Steve Harding, founder and CEO of Showerkap: an innovator.

Emma Mee, Head of Membership at Green Angel Ventures: an investor.

Ghaya Alteneiji, Outreach Manager at The Mohamed Bin Zayed Water Initiative an enabler.

Together, they revealed a hard truth about why water innovation struggles to scale.

The Investability Gap

Water is essential - but it is not easy to invest in.

As Ghaya described it, the sector is trapped in an “investability gap”: the space between urgent human need and what capital markets can actually back.

Water systems are hyper-local, heavily regulated, and politically sensitive. There is no global price, no standard deployment model, and no fast route to scale.

What works in Abu Dhabi won’t work in Manchester. What works in Manchester won’t work in California.

From an investor’s point of view, that creates risk that is hard to price even when the impact is obvious.

Steve sees this every day:

““As soon as someone sees ‘water’, it feels like a slow investment. It becomes harder to have the conversation.””

Water doesn’t behave like software. It moves through utilities, building standards, procurement frameworks, and public infrastructure. Those timelines don’t fit the venture capital playbook even when the technology is strong.

That mismatch is not a market failure. It’s a structural one.

Two Water Markets, Two Bottlenecks

From an investor’s lens, water innovation falls into two very different worlds.

1. Utilities & Industrial Water

Utilities are increasingly open to pilots, grants, and innovation partnerships. Early traction is often easier than people expect.

But scale is where things break.

Rolling out across cities or countries requires long-term buy-in from multiple operators, regulators, and political bodies. That slows adoption precisely when the crisis demands speed.

2. The Built Environment

For technologies like Showerkap, the challenge is even harder.

Buildings are governed by thousands of disconnected decisions - landlords, tenants, developers, and contractors, all with different incentives.

As Steve explained, this creates endless friction for any new water-saving technology, no matter how good it is.

Even worse, water savings in buildings don’t convert neatly into carbon metrics. And in climate finance, what can’t be measured often doesn’t get funded.

Emma’s team works hard to model impact from every angle - but the disconnect still shapes where capital flows.

This is why organisations like The Mohamed Bin Zayed Water Initiative play such a critical role.

The Initiative doesn’t just support innovation, it builds the missing bridges between technology, capital, and deployment.

Their work spans:

Global awareness

Large-scale competitions like the $190M XPRIZE Water Security

Agricultural and urban pilots

Connecting innovators with governments, utilities, and investors

As Ghaya put it:

““Water is essential to every part of the economy - but one of the hardest to invest in.””

The Middle East, especially the UAE, has become a testbed for water technologies the rest of the world will soon need - not as an exception, but as a blueprint.

Beyond Capital: Rethinking the Founder–Investor Relationship

One of the strongest messages from the discussion was that money alone doesn’t move water innovation forward.

Founders need:

Market access

Decision-maker introductions

Policy and regulatory navigation

Long-term partners

And the best investors don’t just provide capital, they provide leverage. That also requires honesty from founders.

Steve spoke about recognising when his own role needed to change:

He could take Showerkap through patents, compliance, and early deployment but scaling required different leadership.

As Emma noted, that level of self-awareness is rare and often what allows an innovation to grow beyond its creator.

Is water a right or a commodity?

The session closed on a deceptively simple question: should water be free?

Steve framed it in behavioural terms: if water is too cheap, waste goes unchecked. If it’s free, infrastructure collapses.

Emma added the nuance: Water must be affordable and accessible but giving it away ignores the realities of treatment, transport, and governance.

Water must be a right but it must also carry value, or the systems that deliver it cannot survive.

From Asymmetry to Alignment

The water crisis is not waiting for better technology.

It is waiting for a financial system capable of funding things that are essential, regulated, local, and slow to scale.

Until we close the investability gap, the world’s most critical climate sector will remain structurally underfunded.

And that is far more dangerous than any drought.